Society Came to a Halt — Even Where the Ground Did Not Shake

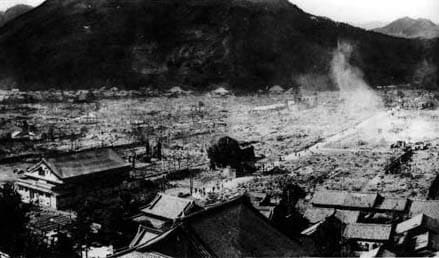

At 4:19 a.m. on December 21, 1946, while Japan was still struggling to recover from the devastation of World War II, the country was struck by another overwhelming force of nature.

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake, with a magnitude of 8.0, caused extensive damage along the Pacific coast of Shikoku, the Kii Peninsula, and parts of western Honshu.

The disaster claimed approximately 1,330 lives, with 11,591 houses completely destroyed and a total of 39,127 homesaffected when including partial collapse, washout, and fire damage.

In addition, a tsunami reaching heights of up to six meters struck coastal areas of Kōchi and Wakayama Prefectures, dramatically expanding the scale of destruction.

However, the most important lesson of the Shōwa Nankai Earthquake lies not only in the physical damage along the coast.

https://www.e-tsunami.com/what_photo2.htm

The Impact Extended Far Beyond the Areas That Shook

Even regions that did not suffer direct building collapse or tsunami damage experienced serious secondary impacts.

Disruption of Logistics

Tsunami damage and ground subsidence severely reduced the functionality of major ports, including Kōchi Port and coastal ports in Wakayama Prefecture.

Key railway arteries such as the Kisei Line and the Dosan Line were cut off for extended periods, severing the lifelines of transportation.

Although logistics networks at the time were far less complex than today’s, delays in the supply of fuel, food, and daily necessities quickly spread beyond the disaster zone into inland urban areas.

Stagnation of Food Supply

Coastal regions of Shikoku and the Kii Peninsula were vital centers of fisheries and agriculture.

Damage to fishing ports, ground subsidence affecting harbor operations, and saltwater intrusion into farmland disrupted food distribution well beyond the affected areas.

Under the postwar rationing system, this was not merely an inconvenience—it directly threatened people’s survival.

Prolonged Suspension of Economic Activity

Factories and commercial facilities in the midst of postwar reconstruction were forced to halt operations even if they were not physically damaged, due to:

- Inability to obtain raw materials

- Restricted movement of workers

- Unstable electricity and communications

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake thus became a disaster that halted economic activity even in regions that were not directly hit.

https://www.e-tsunami.com/what_photo2.htm

A Prototype of Modern BCP and Supply Chain Risk

The clearest lesson the Shōwa Nankai Earthquake offers us today is simple:

Disasters strike not only affected areas, but entire economic systems.

In 1946, terms such as supply chain or business continuity planning (BCP) did not yet exist.

Yet the phenomena that unfolded after the earthquake were structurally identical to what we now discuss in BCP frameworks.

Key localized disruptions included:

- Coastal ports rendered inoperable by tsunami and subsidence

- Long-term shutdown of critical rail corridors transporting goods and people

- Power generation and transmission instability causing repeated operational stoppages

These disruptions did not remain confined to the disaster zone.

Instead, they cascaded outward—raw materials failed to arrive, products could not be shipped, and workers were unable to commute—bringing business activities to a standstill even in areas that suffered no direct damage.

This was, in modern terms:

- Supply chain disruption

- Indirect disaster impact

- Domino-style economic damage

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake clearly exposed how the shutdown of key nodes in specific regions can immobilize an entire economy.

https://www.e-tsunami.com/what_photo2.htm

“Even If You’re Not Hit, Your Business Can Stop”

Nearly 80 years ago, the Shōwa Nankai Earthquake already demonstrated a critical truth:

The safety of one’s own facilities does not guarantee business continuity.

Today, compared to 1946:

- Logistics networks are far more expansive

- Energy systems are more centralized

- Supply chains are deeper and more complex

As a result, the impact of a disaster of similar scale would likely be greater, not smaller.

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake serves as a historical warning against the dangerous assumption that “we’re safe because we didn’t shake.”

Disasters Occur Not as Points, but as Planes

This earthquake teaches us the danger of viewing disasters solely through the lens of epicenters or administrative boundaries.

Disasters spread geographically, economically, and socially—they occur as planes, not points.

Therefore, modern disaster preparedness and BCP must consider not only:

- Whether one’s own facilities will be damaged

- Whether the disaster occurs within one’s municipality

But also:

- Upstream and downstream supply chains

- Availability of alternative routes

- Vulnerabilities of the broader economic region

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake had already revealed that disasters are not isolated events, but stress tests of societal structures.

https://www.e-tsunami.com/what_photo2.htm

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake Is Not Just History

The Shōwa Nankai Earthquake was not merely a major earthquake of the past.

It was a disaster that proved, decades ahead of its time, that:

Even without direct damage, society and business can come to a halt.

As Japan once again faces the risk of a future Nankai Trough megathrust earthquake, this historical event must be reexamined—not as history, but as the origin of modern BCP and supply chain risk awareness.

Product Lineup & Inquiries

▶ Product Lineup

https://sakigakejp.com/en/sales/

▶ Contact Form

https://sakigakejp.com/en/contact-en/